‘Now,” said Georg, snapping me out of my thoughts, ‘there is one further thing that your father has left you, and I must ask you all to come with me. Please, this way.’

We followed Georg, uncertain of where he was taking us, as he led us around the side of the house and across the grounds until we eventually reached Pa Salt’s hidden garden, tucked away behind a line of immaculately clipped yew hedges. We were greeted by a burst of colour from the lavender, lovage and marigolds that always attracted butterflies in the summer. Pa’s favourite bench sat underneath a bower of white roses, and tonight they hung lazily down over where he should have been sitting. He had loved to watch us girls play on the little shingle beach that led from the garden to the lake when we were younger, me clumsily attempting to paddle the small green canoe he had given me for my sixth birthday.

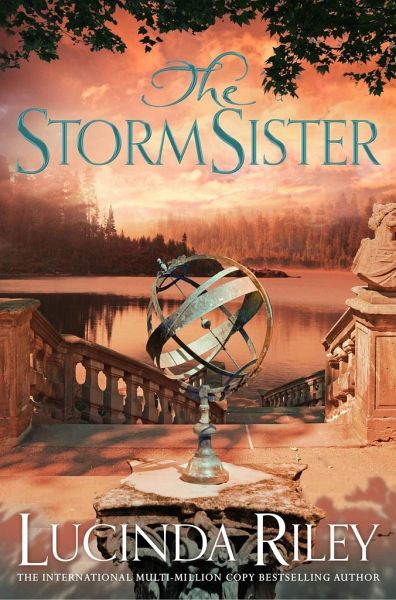

‘This is what I wish to show you, ‘ said Georg, once again pulling me out of my reverie as he pointed to the centre of the terrace. A striking sculpture had appeared there, resting on a stone plinth about as high as my hip, and we all gathered round to have a closer look. A golden ball shot through by a thin metal arrow sat amidst a cluster of metal bands that wound intricately around it. As I noticed the outline of the continents and oceans delicately engraved on the encased golden ball, I realised it was a globe and that the arrowhead was pointing straight to where the North Star would be. A larger metal band looped around the globe’s equator, engraved with the twelve astrological signs of the zodiac. It looked like some kind of ancient navigational tool, but what did Pa mean by it?

‘It’s an armillary sphere, ‘ Georg stated, for the benefit of all of us. He then explained that armillary spheres had existed for thousands of years and that the ancient Greeks had originally used them to determine the positions of the stars, as well as the time of day.

Understanding its use now, I took in the sheer brilliance of the ancient design. We breathed words of admiration, but it was Electra who cut in impatiently, ‘Yes, but what does it have to do with us?’

‘It isn’t part of my remit to explain that,’ said Georg apologetically. ‘Although, if you look closely, you’ll see that all of your names appear on the bands I pointed out just now.’

And there they were, the script defined and elegant on the metal. ‘Here’s yours, Maia.’ I pointed to it. ‘It has numbers after it, which look to me like a set of coordinates,’ I said, turning to my own and studying them. ‘Yes, I’m sure that’s what they are.’

There were further inscriptions beside the coordinates and it was Maia who realised that they were written in Greek, commenting that she would translate them later.

‘Okay, so this is a very nice sculpture and it’s sitting on the terrace,’ CeCe’s patience was wearing thin. ‘But what does it actually mean?’ she asked.

‘Once again, that is not for me to say,’ said Georg. ‘Now, Marina is pouring some champagne on the main terrace, as per your father’s instructions. He wanted all of you to toast his passing. And then after that, I will give you each an envelope from him, which I hope will explain far more than I am able to you.’

Mulling over the possible locations of the coordinates, I walked back to the terrace with the others. We were all muted, trying to take in what our legacy from our father meant. As Ma poured us each a flute of champagne, I wondered how much of this evening’s activities she had already known about, but her face was impassive.

Georg raised his glass in a toast. ‘Please join me in celebrating your father’s remarkable life. I can only tell you that this was the funeral he wished for: all his girls gathered together at Atlantis, the home he was honoured to share with you for all these years.’

“To Pa Salt,’ we said together, raising our glasses.